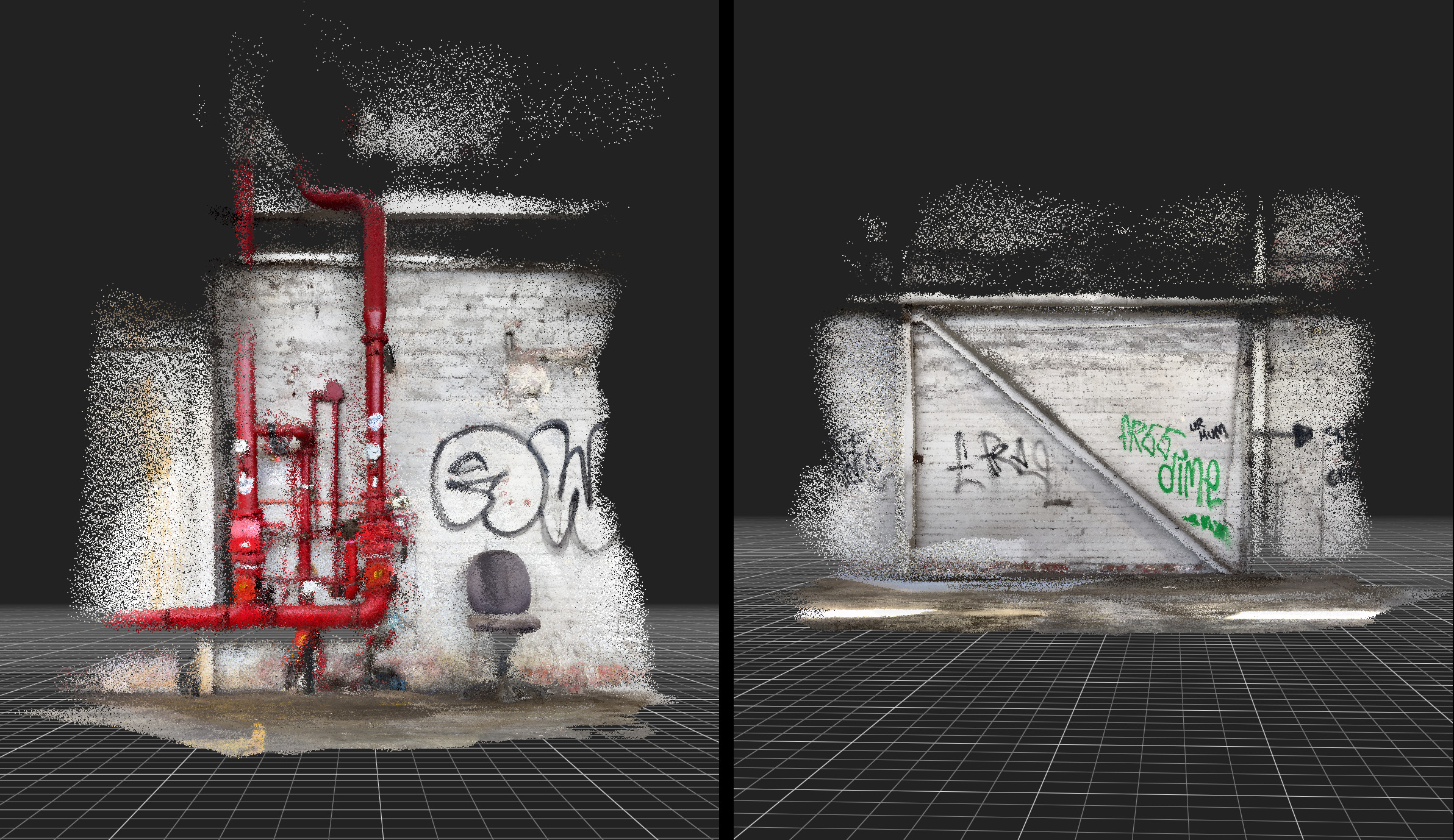

In this latest development, I’ve been working within Unreal Engine to explore how real-world environmental data can drive virtual ecosystems. Using 3D models created through photogrammetry, I’ve been constructing digital landscapes that draw directly from real environments, continuing my ongoing investigation into the relationships between human and nonhuman systems.

|

|

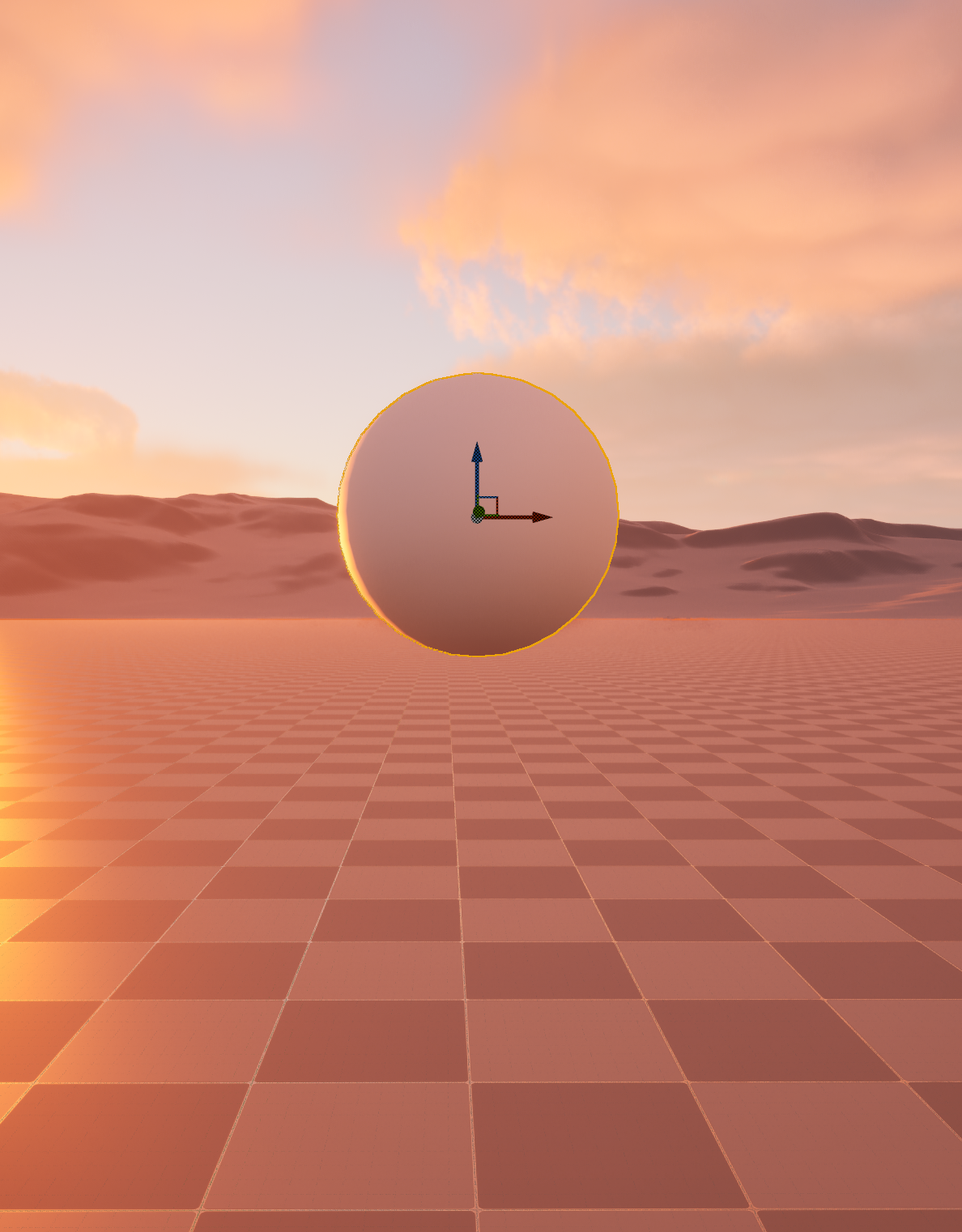

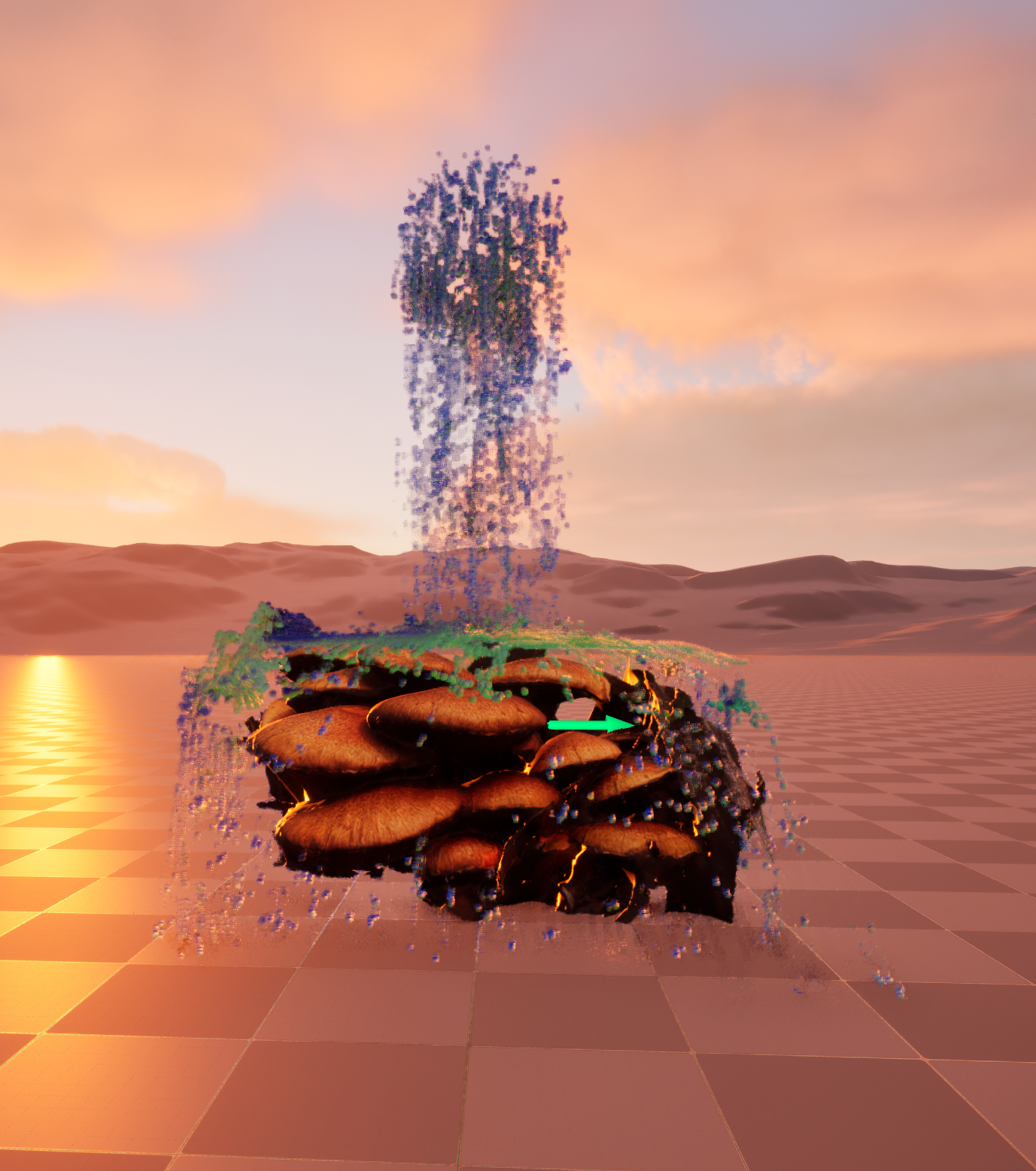

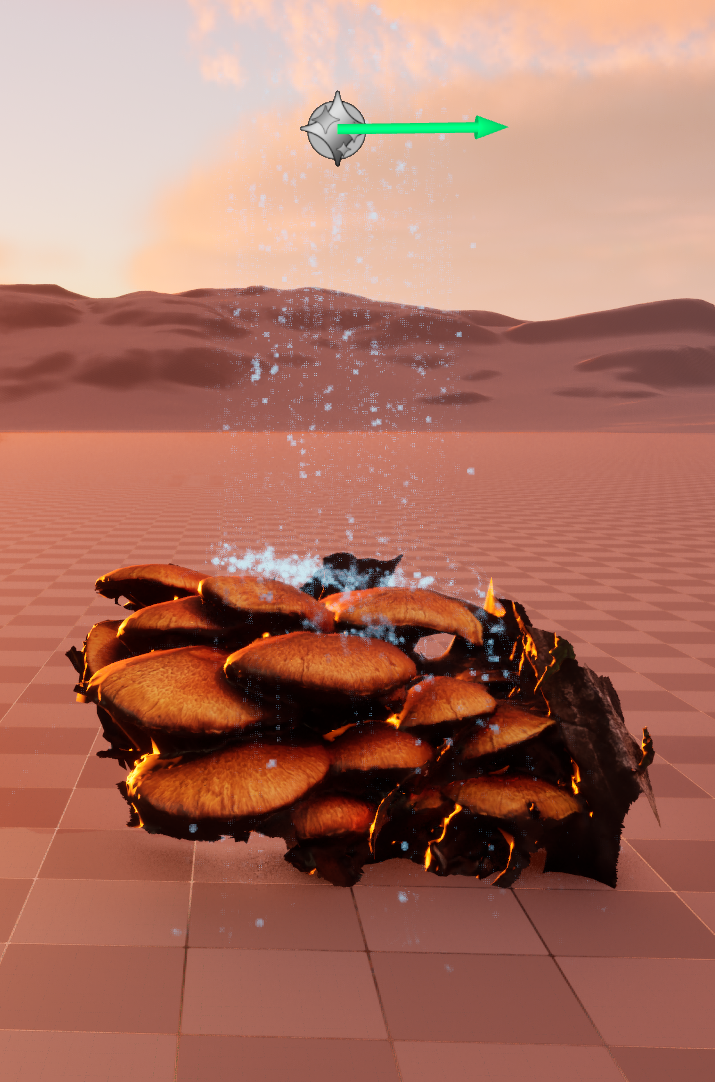

In this Unreal Engine experiment, I focused on simulated water as both a visual and conceptual element. I began by building a series of compositions integrating water bodies into photogrammetry-based environments. The goal was to create a living, responsive system, one that reflects the fluctuations and rhythms of natural water cycles.

To do this, I accessed recorded water data, specifically tidal and reservoir level readings, and connected these data streams to parameters controlling water height, flow, and movement within Unreal. This integration allows the virtual water simulation to shift dynamically, mirroring the variations occurring in the physical world.

By embedding these datasets directly into the Unreal Engine environment, the work moves beyond visual representation into a form of data-driven ecological embodiment, where water, both real and simulated, shapes the work.

This marks the first stage in developing a responsive virtual ecosystem, where environmental data continuously informs visual and performative elements. Going forward, I’ll be expanding this workflow to connect multiple data streams, building toward real-time systems that explore how digital environments can reflect and critically engage with the changing conditions of our planet.